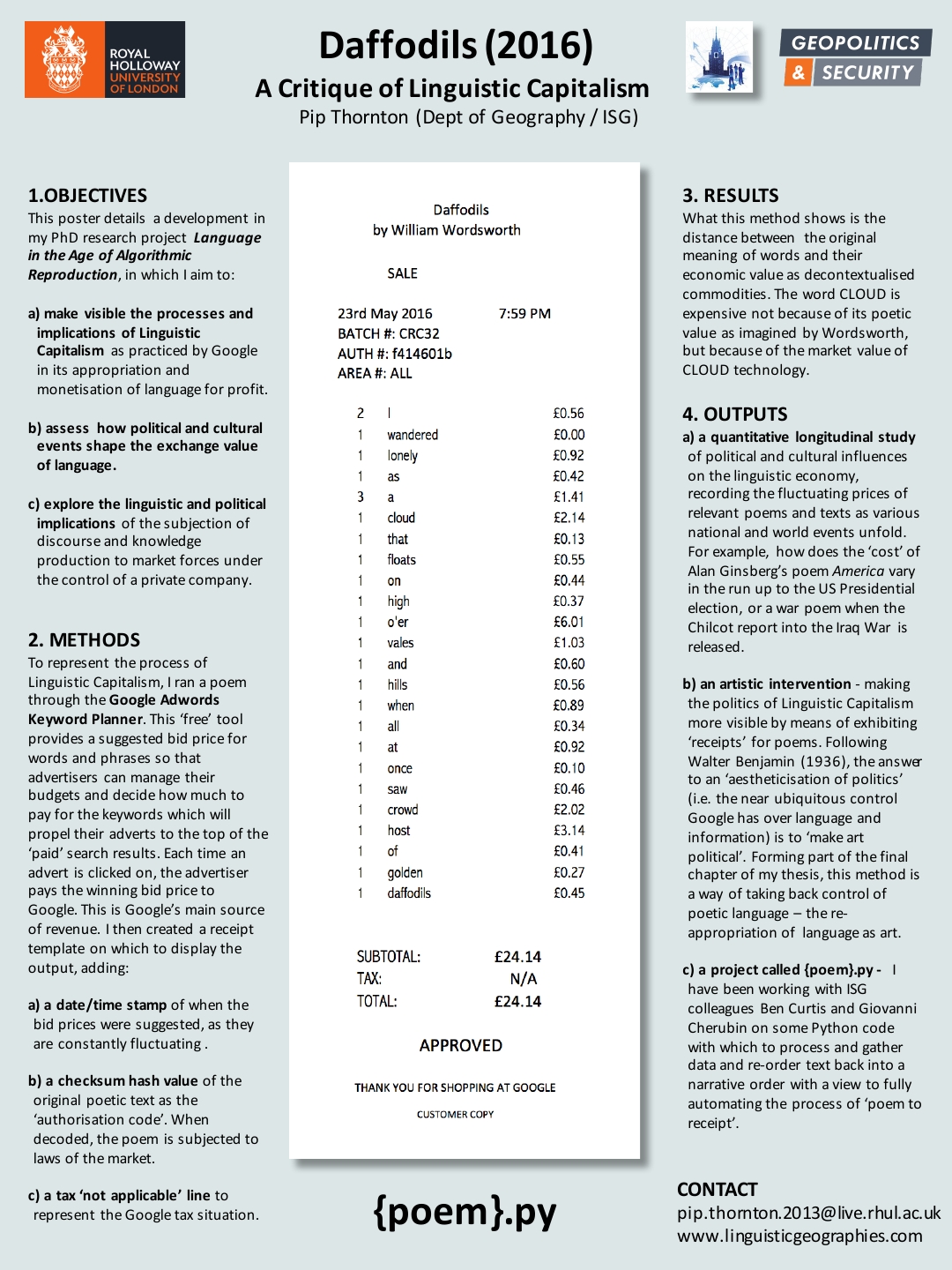

Every time you search for an eligible term on Google, AdWords will run a super-fast auction, and the advertiser with the highest bid on that term gets their ad shown at the top of the search results and pays the winning bid amount every time someone clicks on it. (A few other criteria, such as ad quality, also influence the outcome of the AdWords auction as well as the bid price). The AdWords keyword planner helps advertisers decide how much to bid by offering a suggested price for a given search term. This is what Thornton uses to find the value of poems.

The outcome is often quite interesting, and shows how the AdWords algorithm reduces poetic words to their most economically lucrative meanings. In the Wordsworth example, “cloud” commands a high price not because of the poetic imagery, but because of cloud computing. In the same poem, “crowd” and “host” are quite expensive (£2.02 and £3.14) – because of crowdfunding and web hosting.

Similarly, Wilfred Owen’s Dulce Et Decorum Est includes the word “guttering”, which Owen uses to evoke the sound of a soldier choking in a gas attack. “It’s quite expensive through AdWords, but it’s not to do with the poeticness of the word,” says Thornton. „It’s to do with plastic guttering and drainpipes.”

It is possible to reverse-engineer what Google thinks you’re trying to market, she says, because it will often give you other keyword suggestions. One of the first poems she analysed this way was At the Bomb Testing Site by William E Stafford. Google thought she might be advertising mountain biking, probably thanks to the description of a desert road. It also picked up on the phrase „ready for a change” at the end of the poem. “The algorithm thought it was some kind of recruitment or life coaching thing that I was trying to market,” she says.

Thornton has also run the whole of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four through the system, resulting in a huge roll of till receipt coming to a total of £58,318.14. Part of her inspiration for the project came from Orwell’s fictional language of “Newspeak”. Orwell wrote that many words in Newspeak would be impossible to use “for literary purposes or for political or philosophical discussion.” Thornton’s project shows that the way Google AdWords’ algorithm ascribes meaning to words is “governed by an economic logic rather than a poetic one”.

Sometimes, words have different value in different regions. When visiting Galway in Ireland, for example, someone asked Thornton to make a receipt for Sylvia Plath’s Arrival of the Bee Box. Thornton found that if she specified the region she wanted to advertise to as Galway, the word “god” was worth around three times as much as for the whole of the English marketplace – even though the poem as a whole was much cheaper.

So far, only one person has brought her a poem that AdWords was not able to place a value on, and that’s because it was a spoken-word poem that had not been transcribed online. But as speech-recognition improves and becomes more widely deployed, that might not be so much of a barrier. “Technology’s moving on; speech is being analysed a lot more for these things now,” says Thornton. “But at the time it was brilliant – it’s managed to resist it.”